It's time to revive Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act

Hi there,

Welcome to The Internet is Cool, a newsletter about the invariably strange, infuriating, uplifting, and cool information I find on the Internet.

Today we’re diverging a bit from strictly technology-related phenomena to talk about US politics.

While I was excited to share some research about the porn and sex work industries, it can wait a couple weeks. What I love about writing The Internet is Cool is that I get to learn more about a very specific section of the business or tech world, making connections with topics I’m already familiar with. This time it’s about voting law.

Let’s talk about the link between breeding mistrust in the democratic process and a somewhat obscure piece of protective legislation for voters.

A groundswell of mistrust

Last week, 147 US elected representatives voted “yea” objecting to the Electoral College vote awarding Joe Biden and Kamala Harris the respective presidency and vice presidency. This group of 147 included 139 representatives and 8 senators. All are members of the Republican party.

The vote was an attempt to validate President Donald Trump’s claims that the 2020 election was not free and fair, with Senator Ted Cruz proposing that Congress rush an ethics investigation into its validity. In speeches on the House floor, representatives cited claims from polls that almost 40% of the American public believed the 2020 election was rigged.

This groundswell of mistrust was created, then bolstered, by soon-to-be-former President Donald Trump, his legal team and finally Republicans in Congress themselves. More than two months of false claims by Trump that the election was stolen proved in vain as judges threw out dozens of lawsuits his team and other groups filed, calling them “without merit”—this was his final attempt at delaying the inevitable.

What I’m not going into detail about here is the mob of white nationalists who attended a rally held by Trump where he said, among other things, “you’ll never take back our country with weakness. You have to show strength, and you have to be strong.” They marched over to the Capitol building, interrupting the vote in progress to storm offices with zipties, guns and flash-bangs in hand.

Trump supporters committed an act of violence last Wednesday, and many of them made it home—on planes, to other states—before being arrested.

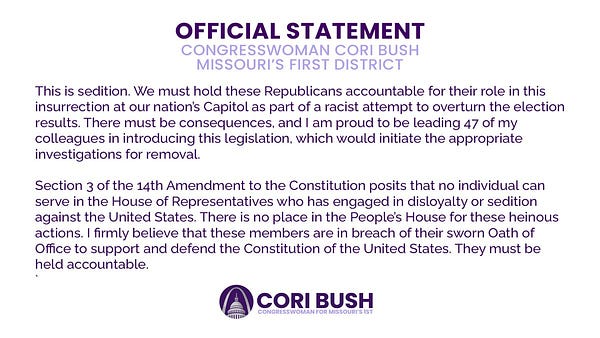

The violence incited by Trump and Congressional Republicans has led many Democrats to call for their removal:

Politicking on claims without merit

But back to the vote: because the House is controlled by the Democrats, the “nays” had it and the objection to the Electoral College vote was not sustained.

There were actually two votes: one on the objection to Arizona’s Electoral College results, and one on the objection to Pennsylvania’s. In both votes and both chambers, the nays led the yeas by a wide margin. Here are the results of the House and Senate votes for the Arizona objection and the House and Senate votes for the Pennsylvania objection.

This procedural objection is not new, nor is it novel. At least one Democrat has objected to the Electoral College vote in every presidential election Republicans have won since 2000. Here’s some historical context, and the comments of this article are interesting to dig into the false equivalency the author makes.

The issue is less members of Congress using a legal way to object to what they see as election irregularities. It is much more Trump refusing to concede, instead claiming widespread fraud without any proof, which riled up his endlessly loyal fan base and gave members of Congress an easy way to say “my constituents demand answers about the validity of this election”—all without substantial evidence that anything was amiss.

So naturally, I was curious who these people were. I’m familiar with Senators Ted Cruz and more recently Josh Hawley, but who are the rest of the senators and representatives who explicitly objected to the 2020 election? What types of districts do they represent? How did their 2020 elections unfold (presumably well, since they won)?

Here’s a spreadsheet I created detailing each representative who objected to the election results.

It includes their name, state, re-election year, and the spread of their most recent election.

It also includes a column for whether they represent a previously a covered jurisdiction under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This means that, from 1965 to 2013, voting laws in that jurisdiction of the US were under a higher level of surveillance due to a history of voter suppression.

What’s Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act?

In case you’re not familiar with the Voting Rights Act (I wasn’t until this summer!), here’s a blurb from the Brennan Center for Justice, an NYU nonprofit law and policy institute:

The Voting Rights Act (VRA) was passed in 1965 to ensure that state and local governments do not deny American citizens the equal right to vote based on their race, color, or membership in a minority language group.

Section 5 of the Act wrote into law a concept called preclearance, instituted to bar certain jurisdictions from passing unconstitutional voter ID laws, literacy tests, or other “devices,” because they suppress turnout from voters of color and in turn favor counting votes from white constituents.

An older example of a “device” that suppresses the vote of citizens who are eligible to vote is a literacy test. In Mississippi these tests included sections on interpreting a section of the state’s constitution and writing an essay about citizenship.

State registrars had wide latitude to decide which section of the state constitution was required, so in practice they could ask a white applicant to interpret a very simple passed, while a Black applicant could be asked to interpret a complex section. Adding to the registrar’s power, “whites were often excused from taking it if, in the opinion of the Registrar, they were ‘of good moral character.’”

Using data from prior elections, the legislation barred discrimination from happening before it could materialize. Section 5 mandated that any changes to voting law in a covered jurisdiction had to be submitted, analyzed for their potential effect on the voting population, then communicated out to constituents.

Potential changes under the microscope included closing polling places, updating a jurisdiction’s list of permissible forms of voter identification, and more niche policies like whether votes cast outside of a voter’s precinct could be thrown out.

Some jurisdictions under preclearance were whole states—Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi to name a few—while others were counties within states, like Collier County in Florida or Yuba County in California.

In 2013, the Supreme Court deemed unconstitutional Section 4b, which contains the formula for determining covered jurisdictions, by a 5-4 majority. Section 5 was not deemed unconstitutional, but effectively gutted by the inability to use the formula outlined in Section 4b.

A protection removed

Chief Justice John Roberts, in his opinion for the majority, held that:

Coverage today is based on decades-old data and eradicated practices. The formula captures States by reference to literacy tests and low voter registration and turnout in the 1960s and early 1970s. But such tests have been banned nationwide for over 40 years…

And voter registration and turnout numbers in the covered States have risen dramatically in the years since… Racial disparity in those numbers was compelling evidence justifying the preclearance remedy and the coverage formula… There is no longer such a disparity.

Why is there no longer such a disparity in states like Mississippi and Alabama where a quick drive through a small town reveals Confederate flags flying? Certainly in large part because of preclearance requirements that prevent discrimination.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s opinion for the minority remarks succinctly,

Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.

While I see some merit in Justice Roberts’ assessment that the formula should be updated, that data from elections in the 1960s and 1970s should be replaced with data from recent elections, the more pressing travesty is the potential suppression of individual voters of color. This interactive map from The New York Times uses variables that could show up in a new version of the coverage formula, as suggested by lawmakers and legal scholars.

Section 5 provides protection for groups that have not seen their equal right to vote realized for a the better part of American history. After Section 5 was ruled unconstitutional in 2013, states previously under preclearance scrambled to pass legislation that would have been blocked in years prior.

When your objection backfires

Because of states’ increased ability to restrict access to voting since 2013, the fraud Republican representatives should be worried about is likely not hurting their party. Increasing the number of polling places, allowing for early voting with varying hours, and pre-registering voters turning 18 before Election Day are all policies that could benefit the Democratic ticket—so some states are attempting the opposite measures.

Around the election, Republican arguments largely centered around the constitutionality of expanding access to absentee and mail-in voting. But that’s a great cover for the real fear that expanding access will benefit Democrats.

Out of Texas this year, from The Atlantic’s reporting:

Republicans have refused to expand mail-in voting except for people age 65 and older, who tend to be more conservative. And last week, Governor Greg Abbott issued a proclamation barring counties from having more than one ballot drop box, a change that will disadvantage counties with the largest, and most diverse, populations.

So object they will. Here are some statements from Republicans who objected during the January 6 vote:

“I urge you to pause and think, what does it say to the nearly half the country that believes this election was rigged if we vote not even to consider the claims of illegality and fraud in this election?”

“Because the Democrats’ campaign of litigation has tainted some states’ elections, I will join in objections to those states’ electors. I consider this to be an obligation of utmost gravity, predicated on my oath to defend the Constitution, and I hope that the controversy at hand will lead to restoring the administration of elections as the Constitution envisions.”

“I came to the Capitol yesterday to give [the protestors] a voice,” he said in a statement. “I joined several Senate colleagues in calling for a bipartisan commission to inspect election issues raised across the country. Our proposal was not successful, but our goal to ensure full confidence and transparency in our elections — for all Americans — is a noble one, and I'll keep pursuing it.”

It’s lovely that our congressmen want to show us how principled they think they are in doggedly pursuing voting irregularities, but the fact stands:

44% of Republicans who objected represent a district that, until 2013, was protected under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act.

In Rep. Bishop’s case, the November 2020 election results he decries re-elected him as representative. But of course it’s not the results from his home state of North Carolina he objects to—he objects to a couple states where Democrats prevailed, and not to any states where the gutting of Section 5 in 2013 could have bolstered performance for the Republican ticket.

Does the same congressman who voted to oppose the Electoral College vote in Pennsylvania also believe Rep. Fred Keller, Rep. Guy Reschenthaler, Rep. John Joyce, Rep. Lloyd Smucker, Rep. Fred Perry, and Rep. Dan Meuser won their Pennsylvania district elections illegitimately? (All 6 also objected to the presidential election results in their own state.)

It is equally funny and horrifying to me that the congressmen above have the audacity to claim that election fraud benefitting Democrats was rampant while representing jurisdictions that are more likely to suffer from election fraud disproportionately benefitting Republicans.

When considering this country’s representation in aggregate, let’s just say the white male Republican vote has not been underrepresented.

Voting law changes disproportionately affect … not Republicans

Earlier we talked about literacy tests, used for years to deny suffrage to Black (and other non-white) would-be voters. Since 2013, emerging forms of voter suppression have no longer been under surveillance by the federal government, and as such states have been shameless in adding these new “devices” into legislation across prior covered jurisdictions.

Fewer than two months after the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision, the state of North Carolina passed legislation including the following:

the number of days of early voting to be reduced (although the total number of hours were required to stay the same as previous elections)

voters prohibited from same-day registration

ballots cast in the wrong precinct to be thrown out

teenagers no longer pre-registered before they turn 18

This legislation resulted in multiple lawsuits, even one from the US Department of Justice, that challenged the state’s far-reaching rollback of voting access. In July 2016, a court of appeals struck it down, noting that it seemed to “target African Americans with almost surgical precision.” While race is not a perfect proxy for political affiliation, in recent elections it’s been a good one.

In the modern era, a commonly debated topic is the closing of polling locations— locations closed are very often in areas disproportionately populated by people of color.

To be fair, a report on poll closure from The Leadership Conference Fund states:

There are justifiable reasons to reduce polling places and consolidations can be executed equitably. But the loss of Section 5 means that there is no process to ensure that reductions are disclosed to the public, are conducted with the input of impacted communities, and do not discriminate against voters of color.

In Texas, the number of polling places dropped from 1 per 4,000 residents in 2012 to 1 per 7,700 residents in 2018. This was in part because the state of Texas was making the transition to vote centers, which is a centralized location where all voters in a given county vote, instead of specific polling places tied to home address. These are theoretically cheaper to operate and might increase turnout for unlikely voters, since voters don’t have to figure out a specific polling place based on address.

But political scientists from the University of Houston found in 2019 that after the county’s transition to vote centers, “more voting locations were closed in Latinx neighborhoods than in non-Latinx neighborhoods, and that Latinx people had to travel farther to vote than non-Hispanic whites.”

Analysis from The Guardian found that:

The 50 counties that gained the most Black and Latinx residents between 2012 and 2018 closed 542 polling sites, compared to just 34 closures in the 50 counties that have gained the fewest black and Latinx residents. This is despite the fact that the population in the former group of counties has risen by 2.5 million people, whereas in the latter category the total population has fallen by over 13,000.

The counties in the former group lost sixteen-fold the amount of polling places that the latter group did, even though that group added more than 2.5 million people to their population.

While I don’t doubt there are some caveats here—a portion of new residents aren’t eligible to vote because of citizenship status or because they’re under 18—it’d be nearly impossible to explain away that entire population gain such that closing 16x (!) more polling places made sense.

To add insult to injury, in 2016, election officials in Texas couldn’t seem to be bothered to provide native-language materials:

A survey conducted by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) concluded that dozens of Texas counties with significant Spanish-speaking constituencies were in violation of the Voting Rights Act for failing to provide information about voting in Spanish.

Another section of the Voting Rights Act, Section 203, explicitly requires the provision of voting materials in a protected group’s native language when that group is more than five percent of all voting age citizens, has a population more than 10,000, or the illiteracy rate of the group is higher than the national illiteracy rate.

New life for Section 5?

Academics and politicians alike have taken up the case of reviving this protective legislation since 2013. Rep. Terri Sewell (D-AL) has introduced a bill attempting to revive Section 5 three times since 2015. It passed the House of Representatives, but with Republican control of the Senate since 2016, it “languished.”

With control of both the House and Senate in Democratic hands until at least January 2023, I’d venture that this year we could see renewed debate of the coverage formula from Section 4b, which, if passed in some form, would revive Section 5 and its protections.

This writing is not to argue that people and public opinion cannot change, that states cannot rid themselves of discriminatory history. The Voting Rights Act even provides for this, stipulating that a jurisdiction covered under Section 5 can be bailed out of coverage after 10 years of elections without issue. Dozens of jurisdictions under preclearance complied and were subsequently bailed out, as noted on the DOJ resource linked above.

It’s clear that public opinion can change, and jurisdictions can evolve to legislate themselves more fairly. But in the meantime, I’d rather have protections in place to prevent disenfranchisement while we’re still hammering out our history of discrimination toward Black people and people of color. And with a brazen man waving the Confederate flag inside the Capitol last week, we’ve got a lot of work to do.