The prickly topic of compensation in remote work

Do we consider location when determining salaries? Should we?

Hi there,

Welcome to The Internet is Cool, a newsletter about the invariably strange, infuriating, uplifting, and cool information I find on the Internet.

On Tuesday, Stripe, the payment processing unicorn, announced that its’ workers were free to relocate—that is, if your definition of free includes a $20,000 one-time bonus but up to a 10% pay cut.

The breakeven salary point for the first year a Stripe employee relocates (where the bonus would be the same as the pay cut they’re taking) is $200,000/year, so this could be a great decision.

That is, it’s a great decision if you’re one of their employees who makes less than that and you’re planning to jump ship in a few months (and if Stripe doesn’t have stipulations on the bonus related to how long you stay after receipt).

Today we’re talking about how remote work could change compensation, specifically for highly-paid tech workers.

Why focus on tech? Several reasons:

It’s what I know

These jobs are easier to complete remotely than most minimum-wage jobs (food service) and some highly-paid jobs (doctors, lawyers)

While sometimes lampooned for its high salaries, the industry’s money changes lives for people from underrepresented groups who train for and secure jobs in the industry

With caveats, they’re highly-paid for a reason, in that “technology is eating the world” + “we have a ton of venture capital money” kind of way

So, let’s talk about tech money and WFH. Questions that come to mind:

Which companies have moved to fully (or “indefinite”) remote work so far? Twitter, Shopify, Zillow and Stripe are some of the significant ones in terms of industry influence. Facebook said yes to WFH, but that’s contingent on workers getting individual approval.

How should we compensate people in this new-ish world? That’s complicated.

Imagine a negotiation-less world

Tech salaries are massive. In the US, New York and San Francisco are the biggest—and highest-paid—tech hubs. The average base salary for a software engineer is $126,000/year in New York and $170,000/year in San Francisco.

Not all companies publish or make explicit this data, but there has to be some fair-ish (emphasis on the ish) way to calculate individual employees’ salaries that takes into account the market rate for the role, the person’s skill level, and the like.

Enter salary formulas.

An oft-cited example of a salary formula done well is by a company called Buffer, which makes social media management software. Their value to “default to transparency” led them to publish their salary formula in 2013, update it (multiple times) by 2019, and keep a living document of all employees’ salaries. Seriously—you can see the CEO’s salary right through that link.

Like most companies that use a publicly-available formula, Buffer’s includes some mixture of the following variables:

base salary for role type

location

seniority

experience

equity vs. more salary (choose one)

It’d then look a little bit like this: (((base salary x location multiplier) x seniority multiplier) x experience multiplier) + equity or more salary

Buffer also made some controversial decisions around paying people more if they supported dependents ($3k per person per year). As of 2016, the company removed that element from the salary formula, presumably because of feedback like the below:

Their rationale was that people with dependents have extra expenses and the $3k/year isn’t enough to incentivize having kids or taking on new dependents. But because it was included in the formula to calculate base salary, this meant employees with families would also receive more equity, which isn’t fair. However, the same $3k/person is now available as a grant you can apply for.

Similarly, GitLab, a DevOps company, utilizes a salary formula that also takes location into account. They attempt to pay a competitive rate for the area where the potential employee is located, which to them means being at or above the 50th percentile for that location.

Not all companies apply a location multiplier, though. Basecamp is a project management software company—they have a salary formula and publish (at least some) data about it. While Buffer benchmarks at the 50th percentile of San Francisco’s rates, Basecamp sets the target at the 90th percentile and doesn’t adjust compensation based on employee location. Here’s how executive David Heinemeier Hansson talks about it:

Raises happen automatically, once per year, when we review market rates. Our target is to pay everyone at the company in the 90th percentile, or top 10%, of the San Francisco market rates, regardless of their role or where they live. So whether you work in customer support or ops or programming or design, you’ll be paid in the top 10% for that position.

If someone is below that target, they get a raise large enough to match the target. If someone is already above the target, they stay where they are. (Nobody will ever see a pay cut because they’re above our market target). If someone is promoted, they get a raise commensurate with the market rates for the new level.

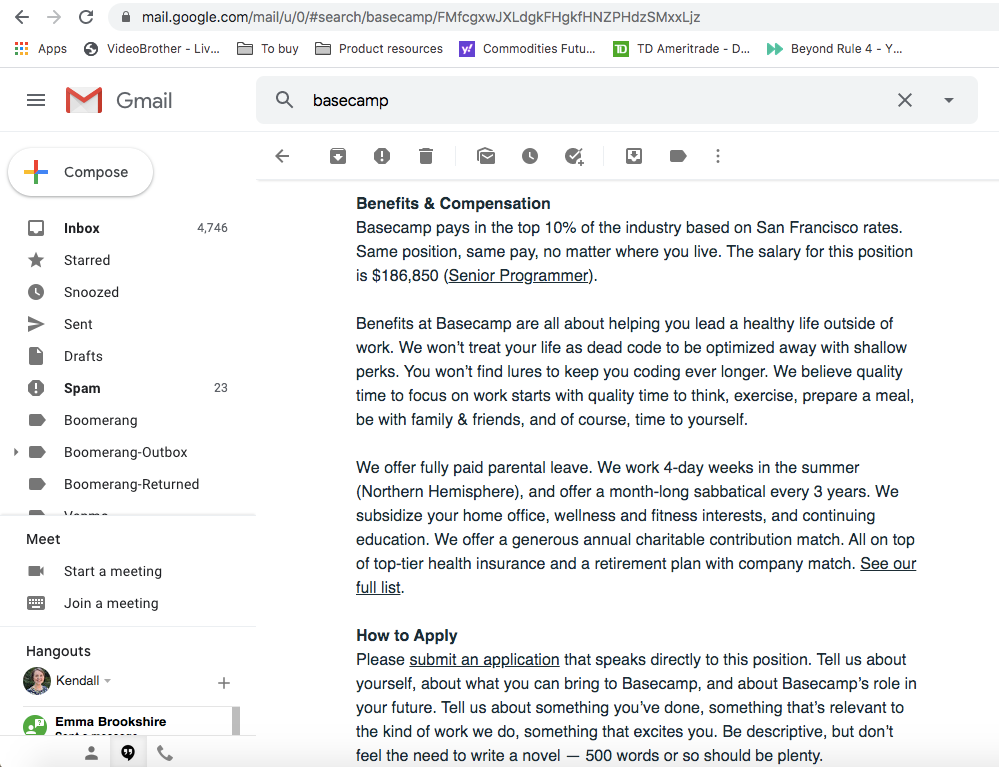

The post quoted is from 2017, but because I’m signed up for Basecamp’s careers email blasts, I can confirm (as of August 5, 2020), that they’re still paying the 90th percentile of SF salaries:

The remote question

What about when employees wise up to their high rents (and, due to Covid-19, minimal opportunities for activity) and want to leave New York or San Francisco?

Like the recent news from Stripe, those fleeing employees might be up for a pay cut.

From Buffer, on their location multiplier:

This multiplier is … applied by using a teammates’ location to determine one of three geographic bands, based on a high, average, or low cost of living area. We use data from Numbeo to figure out which band applies for each teammate. For high cost of living areas we pay 100% of the San Francisco 50th percentile, average is 85%, and low is 75%.

We figure out each teammate’s geographic band by comparing the cost of living index of a teammate’s location to the cost of living index in San Francisco.

From Basecamp, where salaries aren’t adjusted for location:

Our market rates are based on San Francisco. San Francisco is the top of the market for technology businesses. So whether you live in Tennessee or Arizona or Alaska or Illinois, we pay the same. (We don’t even have anyone who works for us from San Francisco!)

This means everyone has the freedom to pick where they want to live, and there’s no penalty for relocating to a cheaper cost-of-living area. We encourage remote and have many employees who’ve lived all over while continuing to work for Basecamp.

And from GitLab, which I found to be the most compelling rationale:

We pay a competitive rate instead of paying the same wage for the same role in different regions. Paying the same wage in different regions would lead to:

If we start paying everyone the highest wage our compensation costs would increase greatly, we can hire fewer people, and we would get less results.

A concentration of team members in low-wage regions, since it is a better deal for them, while we want a geographically diverse team.

Team members in high-wage regions having much less discretionary income than ones in low-wage countries with the same role.

Team members in low-wage regions being in golden handcuffs and sticking around because of the compensation even when they are unhappy, we believe that it is healthy for the company when unhappy people leave.

If we start paying everyone the lowest wage we would not be able to attract and retain people in high-wage regions, we want the largest pool to recruit from as practical.

What’s fair?

Of course Basecamp’s philosophy feels good to a worker: “I can live in a tiny, beautiful, cheap mountain town in North Carolina and still get paid like I live in San Francisco!”

I’m also thinking about how this affects my life. If I end up leaving New York but keep my job remotely, it doesn’t feel fun to accept a “cost of living decrease” based on that move.

There’s also the point that—as noted by my boyfriend Matt as I bounced this idea off of him multiple times—over the next few years, if any significant part of the US workforce switches to remote work and employees start moving en masse to lower-cost areas, employers themselves could wise up and start hiring talented people directly from those lower-cost areas, which means we might see stagnation or depression of market-rate salaries in general.

If Covid-19 democratizes geography of the labor force enough to allow a CEO to hire a whole company of people working remotely for $50,000/year when the company’s current average salary is $80,000, not much beyond warm and fuzzy feelings will make her continue to hire people at the higher rate.

And yet it’ll be interesting to see how many companies—who are scrambling to decide between “remote forever” or “remote for now”—will have a compensation strategy articulated by the time their employees start asking to relocate.

In the final analysis, I feel most aligned with GitLab’s policy on paying competitive salaries for the region, because I find the rationale of attempting to give employees a similar amount of discretionary income and avoiding “golden handcuffs” compelling.

But there’s one example that’s needling at me: when I worked at ClassPass in 2018, we opened a new office in Missoula, Montana, that would come to be the global headquarters. The value proposition was that leadership wanted to find the “next-next” tech hub city, not unlike Denver or Austin 10 years ago. But implicit in that is the difference in cost—it’s cheaper to hire a team of customer service agents in Missoula than New York.

Then our CEO moved there permanently from San Francisco with his family a few months later, citing family ties to the area and a love of the outdoors.

I wonder whether he adjusted his salary down.